This is the second of five posts dealing with the question of ‘The Age of the Earth and the Bible.’ It is taken from the Is Genesis History? Bible Study available in our store. Read the first post here.

Adding up the Genealogies

Starting in the first century A.D. and continuing to the present, most interpreters examined the genealogies in the Bible and said they can be used to calculate the age of the earth.

The first genealogy used this way is in Genesis 5. It reports the age of Adam when he fathered his son Seth, then the age of Seth when he fathered his son Enosh, and so on down to Noah who is said to have been 600 at the start of the Flood. If one sees Genesis 1 as a record of six normal days, and the genealogies as relationships without gaps, then it appears one can calculate the time from Creation to the Flood.

The next genealogy using the same pattern is in Genesis 11. Noah’s son Shem is said to have fathered Arpachshad two years after the Flood. The names and ages continue through Terah, the father of Abram, thereby providing a way to calculate the time between the Flood and Abraham’s birth.

From Abraham forward, it is not as simple a process. There are no longer linear genealogies like the ones in Genesis 5 and 11 listing the father’s age at his son’s birth, so one must track down references to ages at significant events, cross-compare, then calculate together. This process takes one from Abraham to David; from David through the kings of Judah to the Exile; and from the Exile to Jesus’ day.

Once this Biblical timeline is established, specific people and events are seen to intersect with other calendars in the ancient world. These can then be matched to an ‘absolute’ astronomical calendar to determine an approximate age for the earth. For instance, the Jewish historian Josephus, writing around 94 A.D., used this process to calculate the age of the earth as approximately 5500 years from the date of his writing in the first century A.D.

Other men in the early church calculated similar ranges, with estimates provided by Cyprian, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexander, Julius Africanus, Hippolytus, Lactantius, Chrysostom, and Augustine. All of them put the creation of the world as less than 6000 years old from the date of their writing (with many approximating it at 5500 BC).

Prior to the 19th century, almost every significant Biblical commentator thought the Bible spoke to the age of the earth in a definitive way.

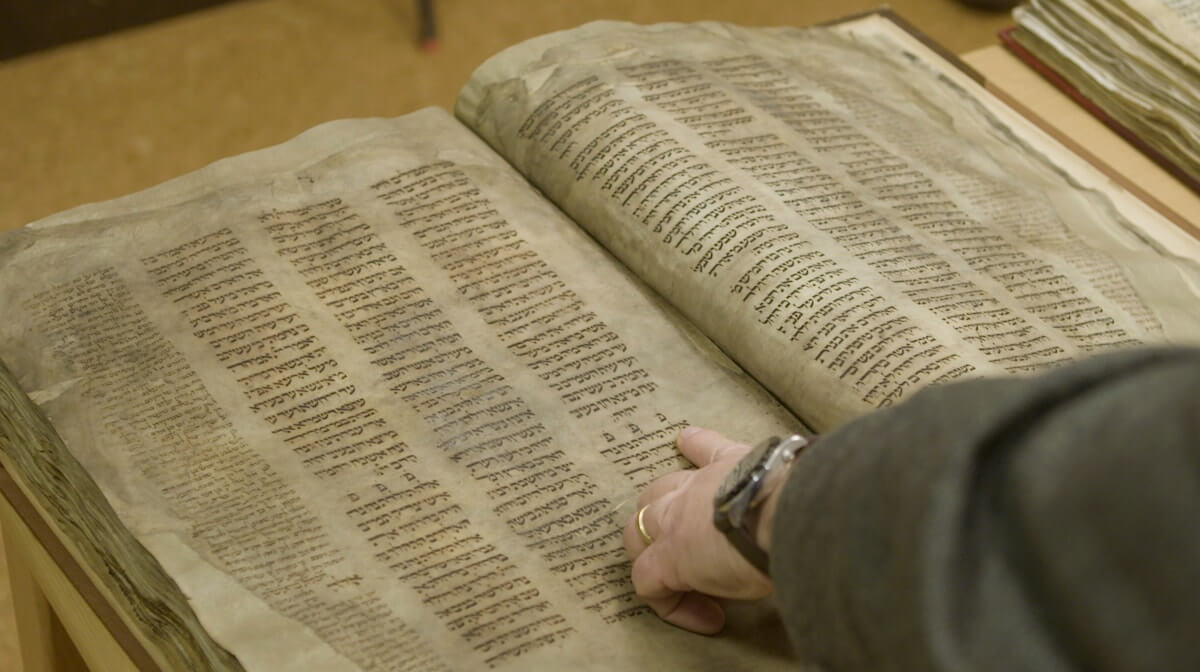

These systems of dating continued through the medieval church and persisted up to the 17th century with the well-known calculation of Archbishop Ussher in England. Like other Protestants, Ussher used the Hebrew ‘Masoretic text’ used by Jewish scribes, a text somewhat different than the older Greek ‘Septuagint’ used in the churches of the first century. This choice resulted in him shrinking the timeline of the world by 1500 years and placing the date of creation at 4004 BC.

Why the difference in age? The Hebrew text of Genesis 5 and 11 often lists younger ages for fathers at their sons’ births in comparison to the Greek text. For instance, in the Greek Septuagint Adam is 230 years old when he has Seth. In the later Hebrew Masoretic text, however, he is 130 years old. The difference in ages adds up to a variation of approximately 1500 years. But where did this difference come from?

Although a complex and controversial topic, it is thought by some that a group of Jews living during the second century AD in Palestine intentionally adjusted some of the numbers in Genesis 5 and 11 in order to keep early Christians from using the age of the earth to calculate Jesus’ arrival as the fulfillment of a messianic prophecy. By subtracting approximately 1500 years from the history of the earth, Jesus would have been born too early to fit into the messianic window.[1]

Today, modern creation scientists and scholars are divided as to whether to accept the longer ages in the older Greek text or the shorter ages in the more recent Hebrew text. The former group places the age of the earth at 7500 years old; the latter at 6000 years old, often still relying on the work of Archbishop Ussher.

Ussher, of course, was just one of many scholars living during his day who, although disagreeing on specifics, ultimately agreed that the age of the earth was less than 10,000 years old. The point is that prior to the 19th century, almost every significant Biblical commentator thought the Bible spoke to the age of the earth in a definitive way.[2]

The Opinions of the New Geologists

In the early 19th century, however, the new sciences of geology and paleontology began to exert an influence on interpretations of Genesis.[3] James Hutton, George Cuvier, Charles Lyell, and others argued that the history of the earth was much older than 10,000 years; they based this view on their new interpretations of the rock layers and the fossils within them.[4]

It became obvious that the traditional view and the new view could not both be accurate since they provided two competing histories of the earth.

This is an important observation: it was not simply a matter of differences in timescale, but of differences in events happening during those timescales. Everyone understood the implications of the profound change in age. In the new view of geology, the earth had a “deep history” with a series of events occurring in it that were radically different than the events recorded in special revelation.

Although non-Christians had already assigned Genesis to the realm of myth, these differences created a major issue for Christians: how did the history in Genesis fit with the new history of the earth? And what did it mean for the doctrines of revelation and creation?

One answer was to question the geological findings themselves. This was done by a series of “scriptural geologists” with limited success, a history that Terry Mortenson documents in his book The Great Turning Point.

The other answer was to change one’s interpretation of Genesis.

New Ways to Interpret an Old Text

As a result, the 19th century saw the introduction of a number of new interpretations that attempted to synthesize Genesis 1 with a much longer period of time.[5] One was the ‘gap’ view which argued there was an indefinitely long period of time between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2.

Another idea was the ‘day-age’ view which said each ‘day’ in Genesis 1 was actually a long period of time. There was much discussion as to just how long a period of time, as well as which events each ‘day’ symbolized, but, in the end, this view provided a symbolic or allegorical function that could be shifted as needed to match changing scientific views.

The result of these interpretations was that, for those who held them, it no longer became possible to determine the age of the earth from the Bible. Instead, it was the role of geologists to determine the age of the earth. This meant that geologists became the new historians of the earth, removing from the Bible the ultimate authority concerning the actual history of creation.

Some commentators and pastors argued this was an incorrect way of interpreting Genesis 1; they said these views were neither in the history of interpretation nor in the text itself. In spite of this, it became more and more popular to interpret Genesis in light of the seemingly indisputable claims of many geologists that the earth was far older than 10,000 years. For some, it was an easy concession because it seemed to maintain the historical integrity of Adam and Eve as well as the rest of the Biblical text.

The one nagging problem was the fossil record.

Read Part 3: Where do Fossils Fit into the Bible?

[1] For more details, see Henry B. Smith, Jr. “MT, SP, or LXX: Deciphering a Chronological and Textual Conundrum in Genesis 5,” Bible and Spade 31.1 (2018), 18-27.

[2] Terry Morteson, The Great Turning Point (Master Books, 2012) 44-45.

[3] Nigel M. de S. Cameron, Evolution and the Authority of the Bible (The Paternoster Press, 1983) 72.

[4] Martin Rudwick, Earth’s Deep History (The University of Chicago, 2014) 99,110.

[5] Mortenson, 33,35.